I'll start with a paradox that anyone who talks to young people about their college majors should understand.

Let's say you're going to college to maximize your future earnings. You've read the census report that says your choice of major can make millions of dollars of difference, so you want to pick the right one. In the end, you're deciding between majoring in finance or nursing. Which one makes you more money?

Correction, 5/24/14: I've just realized I made an error in assigning weights that meant the numbers I gave originally in this post were for heads of household only, not all workers. I'm fixing the text with strikethroughs, because that's what people seem to do, and adding new charts while shrinking the originals down dramatically. None of the conclusions are changed by the mistake.

|

| Original version |

|

| Same chart, all workers |

That means you'll make

Wrong. This is pretty close, instead, to a straightforward case of Simpson's Paradox.* Even though the average finance major makes more than the average nursing major, the average individual will make more in nursing. Read that sentence again: it's bizarre, but true.

How can it be true? Because any individual has to be male or female. (Fine, not really: but for the purposes of government datasets like this, you have to choose one). And when you break down pay by gender, something strange happens:

|

| Original version, head of household only |

|

Male nurses do indeed make less than male finance majors ($72,000

But that's more than offset by the fact that female nurses make much more than their finance counterparts ($64,000

So why the difference? Because there are hardly any men who major in nursing, and hardly any women who major in finance, so the median income ends up being about male wages for finance, and about female wages for nursing.

|

| Original version, heads of household only. |

The apparent gulf between finance and nursing has nothing to do with the actual majors, and everything to do with the pervasive gender gaps across the American economy.

Like many examples of Simpson's paradox, this has some real-world implications. There's a real push (that census report is just one example) to think of college majors more vocationally. Charts of income by major are omnipresent. There's even a real danger that universities will get some federal regulation using loan repayment rates, which won't be independent of income, to determine what colleges are doing a "good" or "bad" job.

Every newspaper chart or college loan program that doesn't disaggregate by gender is going to make the majors that women choose look worse than the ones that men choose. Think we need more people to major in computer science, engineering, and economics? Think we need fewer sociology, English, and Liberal Arts majors? That's not just saying that high-paying fields are better: it's also saying that the sort of fields women major in more often are less worthwhile.

How important is gender? Very. A male English major

By the way: you might be thinking, "That's great: the ACS includes major, now we have some real evidence." You shouldn't. Data collection isn't apolitical. The reason that the ACS includes major is because the state has turned its gaze to college major as a conceivable area of government regulation. We're going to get a lot of thoughtlessly anti-humanities findings out of this set: For example, that census department report grandly concluded that people who major in the humanities are much less likely to find full-time, year-round employment, while burying in a footnote that schoolteachers--the top or second-most common job for most humanities majors--don't count as year-round employees because they take the summer off. **** So, brace yourself. One of the big red herrings will be focusing on earnings for 23-year-olds; this ignores both the fact that law (which you can't start until age 26) is a common and lucrative destination for humanities majors, but also that liberal arts majors catch up, since their skills (to speak of it instrumentally) don't atrophy as quickly. Not to mention all the non-pecuniary rewards.*****

So one of the big challenges over the next few years for advocates of fields that include a lot of women (which includes psychology, education, and communication, as well as many of the humanities) is going to be sussing out the implication of the gender gap for proposed policies and regulations. A perfectly crafted higher ed policy would, of course, take this into account: but it's extremely unlikely that we'll get one of those, if indeed we need one. It would be a bitterly ironic outcome if attempts to fix college majors ended up rewarding fields like computer science for becoming systematically less friendly to women over the last few decades.

This isn't to say there aren't real effects: pharmacology and electrical engineering majors do make more money, certainly, than arts or communications majors. But while the gender disparity is a massive, critical element to every discussion of wages, it's not the only thing lurking behind these numbers. (I've only imperfected adjusted for age, for example).

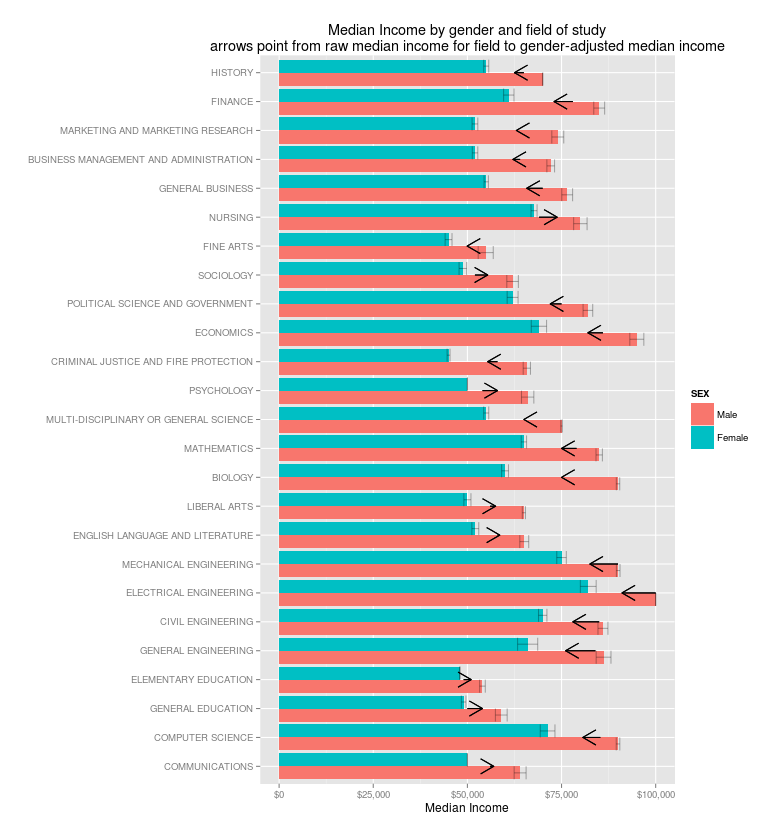

So I'm reluctant to give the average incomes at all, since I suspect that even with gender factored out they might confuse us. Still, it's worth thinking about. So here they are: a chart of the most common majors, showing median income for men and women: the arrows show the shift from the actual median income to what it would be if both genders were equally represented.

|

| Original version: heads of household only. |

*Actually, this isn't a perfect case of Simpson's paradox, because the male rate is indeed lower; there's a third variable at play here, the size of the gender gap within each field: although it's everywhere, the gender gap isn't necessarily the same size.

**Median incomes usually come out as round numbers, because most people report it approximately; but sometimes, as here, they don't.

***I don't actually recommend you do precisely that, from a lobbying perspective.

**** That's why I've made the somewhat questionable choice of not reducing the set down to "full time year round" workers as is conventional: instead, I'm using the weaker filter of persons under 60 with a college degree who worked at least 30 hours a week.

***** Which, yes, I believe are more important than the few thousand dollars you might get by agreeing to sell pharmaceuticals the rest of your life. But it's critically important not to just cede the field on less exalted measured of success.

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDeleteRe: "the real thing holding back most English majors in the workplace isn't their degree but systemic discrimination against their sex in the American economy."

ReplyDeleteYou seem to be a discriminationist who is blindly determined to interpret women's and men's job-related choices as discrimination against women.

Here are two of countless examples showing that some of America's most sophisticated women CHOOSE to earn less:

"...[O]nly 35 percent of women who have earned MBAs after getting a bachelor’s degree from a top school are working full time." It "is not surprising that women are not showing up more often in corporations’ top ranks." http://malemattersusa.wordpress.com/2014/04/25/why-women-are-leaving-the-workforce-in-record-numbers/

“In 2011, 22% of male physicians and 44% of female physicians worked less than full time, up from 7% of men and 29% of women from Cejka’s 2005 survey.” ama-assn.org/amednews/2012/03/26/bil10326.htm (See also "Female Docs See Fewer Patients, Earn $55,000 Less Than Men" http://finance.yahoo.com/news/female-docs-see-fewer-patients-172100718.html

If millions of women as stay-at-home wives are able to accept NO wages, millions of other wives, whose husbands' incomes vary, are more often able than husbands to:

-accept low wages

-refuse overtime and promotions

-choose jobs based on interest first, wages second — the reverse of what men tend to do (The leading job for American women as of 2010 is -- has been for over 40 years -- secretary or administrative assistant. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/06/11/gender-wage-gap_n_3424084.html)

-take more unpaid days off

-avoid uncomfortable wage-bargaining (tinyurl.com/3a5nlay)

-work fewer hours on average than men (http://www.bls.gov/news.release/atus.nr0.htm), or work less than full-time more often than their male counterparts (as in the above example regarding physicians)

Until you examine the influence a husband's income has on wives and single women who intend to marry, you will continue to create problems where none exist and offer solutions that don't solve. Your only achievement will be ot drive the wedge deeper between the sexes.

Here's what I don't have time to say:

“The Doctrinaire Institute for Women's Policy Research: A Comprehensive Look at Gender Equality” http://malemattersusa.wordpress.com/2012/02/16/the-doctrinaire-institute-for-womens-policy-research/

Excerpt:

Because of gender roles, the sexes as groups have a different psychology about money and work. The difference produces this:

-Far more men than women link their self-worth to their net-worth.

-Far more women than men seek spouses with a high net-worth (hypergamy)

-Far more single women than single men ask prospective dates, "What do you do?" And they listen more closely to the answer.

-Far more women than men expect their spouse to be the primary provider who will give them the option of staying at home to raise the children, while the spouse raises the income that pays her to raise the children.

-Far more women look at a prospective spouse as an "employer" who will pay them to stay at home when they choose to do so.

I should say first that the mechanics of the gender gap don't matter at all for the core argument here: our impressions of which majors make more money are shaped by the gender gap, regardless of its cause.

DeleteThat said: Men made $5 billion in the US and women $3.2 billion from 2010 to 2012. Certainly, some of the gap is due to choices like the ones above.

But it takes far more "blind determination" to think that all the gap comes from personal choices than to think it comes from a mix of choices and systemic biases. Even some of the things you describe sound more like bias than choices to me. For example, you're right that women appear to negotiate less effectively than men. But it seems crazy to me to say "women choose to negotiate less and make less money" in the same way one might reasonably say "women choose to raise children rather than work." Rather, I'd take that to mean "norms around salary negotiations are structured in ways that disproportionately reward men." If we could fix that, we should.

Well, the problem is that studies that look at subfields and individual job titles show much less of a difference, and none for some. (And a few extremely rare jobs where women make more due to stereotypes-- such as playing the harp.) Fields like pharmacy, where these days the vast majority of pharmacists are employees of big companies and work regular, structured hours, show almost no difference. The difference among physicians have declined precisely as more physicians have moved towards being hospital employees rather than partners in private practice.

DeleteAnd certainly we can say *all* of those choices (including which parent raises children) are shaped by systemic and societal biases, but it makes a great deal of difference as to what sort of policy recommendations one would make.

The evidence for bias in the sense of employer decisions or people being "paid less for the same work" is close to zero. The evidence for bias in the sense of "society encourages men to take more risk and sacrifice personal life for career, and women to do the reverse" is strong.

When women no longer have to make careers choices based on the amount of workplace discrimination they will face as *child bearers*, then let's talk about it, Male Matters. We don't "choose" to take more unpaid days off--we are forced to. And many of my "stay-at-home mom" friends would prefer to work, but child care costs exceed what they would earn. But hey, we can all choose to no longer have kids. Then the problem will be solved, yes? *sigh*

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDeleteMaybe I just missed it, but I am not seeing the citation for where you got your chart data. Where did these numbers come from? Do you have a link? An article?

ReplyDeleteSorry, just noticed this question in the spam file and I see I just said "ACS." Data is from the American Community Survey, 2010-2012 public use microdata files. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/data/pums.html

DeleteMaybe I just missed it, but I am not seeing the citation for where you got your chart data. Where did these numbers come from? Do you have a link? An article?

ReplyDelete