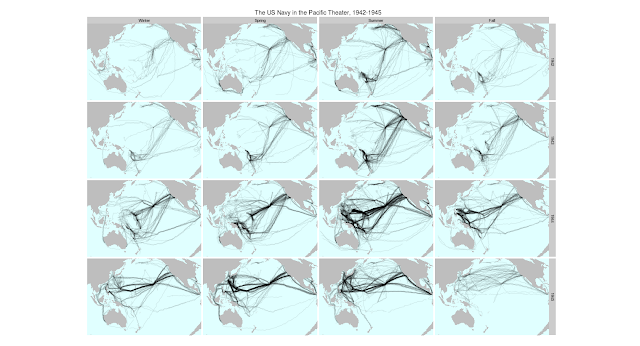

[Temporary note, March 2015: those arriving from reddit may also be interested in

this post, which has a bit more about the specific image and a few more like it.]

Digitization makes the most traditional forms of humanistic scholarship more necessary, not less. But the differences mean that we need to

reinvent, not

reaffirm, the way that historians do history.

This month, I've posted several different essays about ship's logs. These all grew out of a single post; so I want to wrap up the series with an introduction to the full set. The motivation for the series is that a medium-sized data set like Maury's 19th century logs (with 'merely' millions of points) lets us think through in microcosm the general problems of reading historical data. So I want in this post to walk through the various parts I've posted to date as a single essay in how we can use digital data for historical analysis.

The central conclusion is this: To do humanistic readings of digital data, we cannot rely on

either traditional humanistic competency or technical expertise from the sciences. This presents a challenge for the execution of research projects on digital sources: research-center driven models for digital humanistic resource, which are not uncommon, presume that traditional humanists can bring their interpretive skills to bear on sources presented by others.

|

|

| All voyages from the ICOADS US Maury collection.

Ships tracks in black, plotted on a white background, show the

outlines of the continents and the predominant tracks on the trade

winds. | | | | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

We need to rejuvenate three traditional practices: first, a

source criticism that explains what's in the data; second, a

hermeneutics that lets us read data into a meaningful form; and third,

situated argumentation that ties the data in to live questions in their field.