To quickly recap: I take a word or phrase—evolution, for example—and then find words that appear disproportionately often, according to TF-IDF scores, in the books that use evolution the most. (I just use an arbitrary cap to choose those books--it's 60 books for these charts here. I don't think that's the best possible implementation, but given my processing power it's not terrible). Then I take each of those words, and find words that appear disproportionately in the books that use both evolution and the target word most frequently. This process can be iterated any number of times as we learn about more words that appear frequently—"evolution"–"sociology" comes out of the first batch, but it might suggest "evolution"–"Hegel" for the second, and that in turn might suggest "evolution" –"Kant" for the third. (I'm using colors to indicate at what point in the search process a word turned up: Red for words that associated with the original word on its own, down to light blue for ones that turned up only in the later stages of searching).

Often, I'll get the same results for several different search terms—that's what I'm relying on. I use a force-directed placement algorithm to put the words into a chart based on their connections to other words. Essentially, I create a social network where a term like "social" is friends with "ethical" because "social" is one of the most distinguishing terms in books that score highly on a search for "evolution"–"social", and "ethical" is one of the most distinguishing terms in books that score highly on a search for "evolution"–"ethical". (The algorithm is actually a little more complicated than that, thought maybe not for the better). So for evolution, the chart looks like this. (click-enlarge)

Small changes in the algorithm (how deep to search on the first go-round, how many books to look in) have substantial implications for how it turns out, which is kind of a problem. You'll see that this evolution chart looks somewhat different from the earlier one. There's a fair amount of computing for each chart (15 minutes), so I just plugged in a few words I find interesting a few nights ago to see how they turned out and what sort of different results we can get. As always, this is on a set of books by American publishers from 1830 to 1922, heavily weighted towards the 1880-1920 period. Let's look at a few:

Wherever I search for evolution, I eventually search for efficiency as well. This one worked very well in mapping out different 'discourses' using the term. Government on the lower right, railroads and other corporations on the lower left, more generally industry in the center, education prominent in the upper right and blurring into the language of the social sciences. This one is just fascinating; the next step with something like this would be to figure out a good way of letting it move temporally, to see if some of these clusters are more active earlier and some more active later. One way to do that would be to use correlation charts on some of the terms to see, for example, when the educational language is most heavily associated with efficiency, but there are more precise ways, I'm sure. Overall, I'd say this is the case where the clustering algorithm best does what I'd want it to.

Union and Confederacy. This is a search term I used earlier to distinguish Civil War–related books. You can see that these terms arrange themselves into two groups—words more directly related to war on the left, and more political ones (including several connected to other periods in US history) to the right. I should be using some measures of network 'tightness' to see if this is more diffuse or tighter than evolution. The oblong rather than round shape indicates less connection between the two opposite ends, for sure.

I was interested in Ted Underwood's reflections on color and sensory language, so I tried putting in red, blue and yellow to see their associates. It's instructive of some of the limitations of using search terms naïvely. Certain types of words are inherently more packed into certain books, and they tend to do much better on TF-IDF search. Looking for colors, we get not more colors but two largely unconnected spheres of language built around chemistry and biology/botany, respectively. Those are intense discursive spheres, to be sure, but 'color' itself is not central to either of them. This system might work better on terms that have high overall TF-IDF scores, so that we're searching among comparables: or I could build in some sort of limitations to find truly similar words, rather than merely associated words. In some cases, that might be useful, but I can't immediately imagine one.

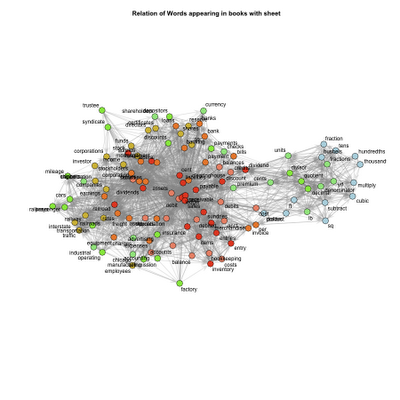

I put in "sheet" as a word with a lot of different meanings, and it turned out mostly business-related ones, with a smaller cluster of math terms that still probably come mostly out of accounting. Like the color example, this highlights the tendency of my algorithm, at the moment, to fixate on one or two particular subsets of discourses if they predominate rather than necessarily picking up on alternate usages if they are much smaller in number.

This makes an interesting comparison to the scatter chart I did earlier on scientific method. We get many of the same terms, but now ordered by some sort of semantic groups. At the heart, we get terms like "Comte", "Hypothesis,", and "Objective" that are key to much of the discourse: and sciences like psychology and sociology turn out much more central than biology or chemistry, which I talked about a little then. The philosophers are at the right, the evolutionists at the bottom, and education forms a markedly distinct sphere off to the left.

What if we use a word that actually defines a discipline, like sociology? We get yet another educational corner off in lower right, some obvious sociology and psychology concepts in the center, with Spencer a bit more central than Comte even though he shows up later in the search process (being orange rather than pink, that is).

Psychology takes a much more spherical shape, which I suppose might indicate a little more continuity among the different spheres (or perhaps just a larger number). The red and orange terms, the ones that show up first in the search process, are a little more evenly distributed along the periphery than in some other searches. I'm actually quite surprised the educational discourse didn't pop out markedly on this one, too.

Attention divides itself into two separate groups, and the bottom one is almost all blue-green, meaning it didn't show up until later. I found earlier that medicine was one of the fields using the word 'attention' the most, and that's what's taken over the bottom. Another problem of colonization by a particular term, probably on the basis of diagnostic manuals or something like ("pay attention to the tissue lesions in making a prognosis" that rather than any particular deep insight into attention as a psychological phenomenon. There's no way to count this one as a success.

I thought I'd try a person, so why not Abraham Lincoln? We get two clusters here: one on the left that nicely parcels out the various parts of his career, and one on the left that shows why separately searching for Abraham and Lincoln isn't as good as using the bigram—you end up with things that just have a lot of proper names and months. I could check what that genre is, but I think better is to move along with looking at the data and addressing a few other issues I want to get at (including Ted Underwood's idea of using chronological groups for clustering instead of word-associates). But if anyone has some requests for seed words to use for this sort of clustering, let me know and I'll post them.

I feel like this process actually works pretty reliably at what it does -- which is to identify the discourses where a particular (set of) term(s) is *most* prominent.

ReplyDeleteEven in the case of color, I feel I'm learning something. I wouldn't necessarily have guessed biology or chemistry.