Back in 2013, I wrote a few blog post arguing that the media was hyperventilating about a "crisis" in the humanities, when, in fact, the long term trends were not especially alarming. I made two claims them: 1. The biggest drop in humanities degrees relative to other degrees in the last 50 years happened between 1970 and 1985, and were steady from 1985 to 2011; as a proportion of the population, humanities majors exploded. 2) The entirety of the long term decline from 1950 to 2010 had to do with the changing majors of women, while men's humanities interest did not change.

I drew two inference from this. The first was: don't panic, because the long-term state of the humanities is fairly stable. Second: since degrees were steady between 1985 and 2005, it's extremely unlikely that changes in those years are responsible for driving students away. So stop complaining about "postmodernism," or African-American studies: the consolidation of those fields actually coincided with a long period of stability.

I stand by the second point. The first, though, can change with new information. I've been watching the data for the last five years to see whether things really are especially catastrophic for humanities majors. I tried to hedge my bets at the time:

It seems totally possible to me that the OECD-wide employment crisis for 20-somethings has caused a drop in humanities degrees. But it's also very hard to prove: degrees take four years, and the numbers aren't yet out for the students that entered college after 2008.But I may not have hedged it enough. The last five years have been brutal for almost every major in the humanities--it's no longer reasonable to speculate that we are fluctuating around a long term average. So at this point, I want to explain why I am now much more pessimistic about the state of humanities majors than I was five years ago. I'll show a few charts, but here's the one that most inflects my thinking.

One thing I learned in a humanities field is that people with strong opinions are always eager for a crisis because it gives a chance to trot out solutions they came up with years earlier. Little-c conservatives tend to argue that the humanities must return to some set of past practices: teaching Great Works or military history. As I said above, these arguments tend to be misguided--they often assume laughable propositions (yes, colleges still teach Shakespeare), and they don't match the contours of the humanities' decline. Practicing academics tend to write pieces arguing that some pedagogical tactic they've found to work (flipped classrooms! joint majors with CS! community integration! non-traditional assignments!) needs to be more widely adopted. Big-picture thinkers argue that we need to "make the case" for the skills taught in humanities fields, since a society where citizens lack empathy (which you get from reading novels) or a sense of their history (which is often generalized into a pan-humanities virtue) or an ability to realize a figured base at the keyboard (which is what I spent my humanities credits on) is an impoverished and endangered one.

I don't have a solution to peddle. But the drop in majors since 2008 has been so intense that I now think there is, in the only meaningful sense of the word, a crisis. That is: we are in a momentum of rapid change in which decisions are especially important, and will have continuing ramifications. If you still have the same opinions you did in 2010 or 2013, it's worth reassessing the situation. Unless current trends reverse rapidly and for several years, humanities education in the 2020s will have to be different than it was in the 2000s.

Here are the general points.

1. No matter what baseline you use, virtually every humanities major from big, old ones like English to

2. Rather than recover with the economy, that decline accelerated around 2011-2012. That period constitutes an inflection point for a variety of majors in and out of the humanities. Though it may have slowed a bit in the last few years, there's little sign that the new post-2011 universe holds signs of a turnaround.

3. More humanistic social sciences like sociology or political science are also caught in the undertow: the big winners are mostly concentrated in the STEM fields.

4. These trends are widespread across institutions that they may reflect student preferences formed before they see a college classroom.

The rest of this will spell out some of the data based on preliminary IPEDS releases from the Department of Education. In all cases I'm working directly from the raw data. The code I use for parsing is here. Particularly for 2017 statistics, there have not yet been any government publications giving aggregates. I generally use the American Academy of Arts and Sciences taxonomy of the humanities with one major exception: I don't consider communications to be a humanities discipline. Sometimes I see humanists suggesting that things must be better in the areas where we don't have measurements, often with reference to local anecdotes.

Within colleges and universities, the humanities are testing new lows

The fundamental reason I've changed my mind has to do with the two following charts. In 2013, I posted the following chart of long term trends since 1948. It showed that the long-term trends were steady. There's a small sign of a drop off after 2008: but because I mostly formed my ideas about these trends in 2005, I explained it away as unimportant.

Now look at the last 6 years of data. The slope from 2011 has become a cliff. Where in the 2000s about 7.5% of students had one of the big four humanities majors, now less than 5% do.

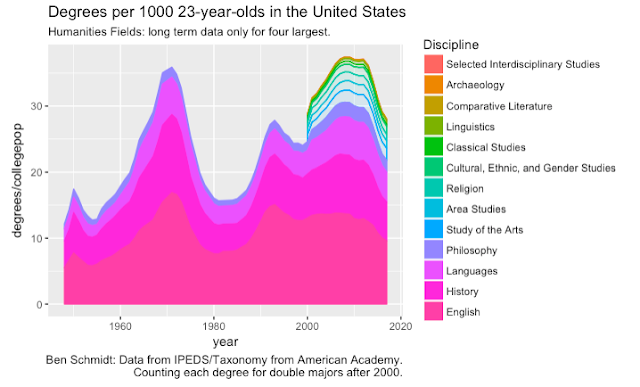

The big picture, I think, is: after the boom and bust of the 60s and 70s, the humanities entered a long period of stability from about 1990 to 2010 or so. That period has ended, and now we're entering a new one in which levels will be very different. We'll obviously stabilize somewhere, probably in the next few years, and maybe we'll rebound a bit, but I'd be very surprised if humanities numbers in five years were even 2/3 what they were in 2005.There are, of course, other majors than these four. Here are all of the fields classed as "humanities" by the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. (Thanks to Rob Townsend for sending their list my way. It's worth noting here that I developed my acquaintance with this dataset working on the first version of the humanities indicators at the Academy in 2005.) According to their taxonomy, every field but humanistic subfields of communications and linguistics (the two fields with the weakest claims to actually being "humanities") has seen substantial drops in share since 2009. EDIT: Not sure why I missed this, but I just noticed that "cultural, ethnic, and gender studies" are also stable. This is a very small percentage of the humanities (all put together, maybe a tenth of English), but an important caveat nonetheless.

You can also see in these charts how recent the shift is. Although English has been in steady decline for an extraordinarily long time (practically unchecked since the mid-1990s), fields like history, philosophy, and classics were booming before 2008.

The decline is not strongly related to the expansion of higher ed.

"Share" can be a funny way to think about colleges, though, since the field of higher education itself is constantly expanding.So here's the most optimistic take I can give. It shows the 70-year story, which is full of radical ups and downs. The y-axis gives the number of degrees per one thousand 23-year-olds in the country. Since the 2011 results, the humanities have fallen from 37.1 degrees per thousand adults to 28.0 (about a 25% drop); the big four, for which I have data back to the 1940s, have fallen from 29.8 to 21.7 per thousand (a 27% drop). This exceeds all but one previous fall in humanities majors: the drop in the 1970s.

That 1970s drop, I argued, coincided with the opening of professional fields to woman and the quick deflation of the big boomer bubble of the late 1960s, in which first-generation college students seem to have piled into humanities majors at schools across the country. The question is: why the drop since 2008?

Even looking at raw numbers, the past decade shows a sharp decline.

Even by raw numbers--which is not an especially useful baseline in a growing country--you can see a massive shift since 2011. Here I've pegged each major to its maximum year: that was 2009 for English, 2010 for history, and 2011/2012 for the other fields. This makes the shape of the changes abruptly clear--the raw number of English and History majors is down more than a quarter from these extremely recent peaks. On the other hand, all fields except the two largest are at least absolutely higher than in 2000.

It's not just humanities fields

I occasionally worry that talk of the "humanities crisis" could be a self-fulfilling prophecy. Fortunately or unfortunately, though, the shift seems to have more to do with content than with labels. The social science fields that most closely resemble humanistic ones--sociology, anthropology, international relations, and political science--have also seen serious drops. Here are 22 fields that I track. I've put a line at 2011 because it's frequently an inflection point--you also see many shifts around 2008 and 2015 or so.

The big winners in recent years have been health professions, including nursing; computer science and engineering; biological science and to a lesser degree, physical sciences; and what I oddly call "leisure," which includes things like sports management and exercise studies.

The big winners in recent years have been health professions, including nursing; computer science and engineering; biological science and to a lesser degree, physical sciences; and what I oddly call "leisure," which includes things like sports management and exercise studies.

The trend is stronger higher up the prestige chain.

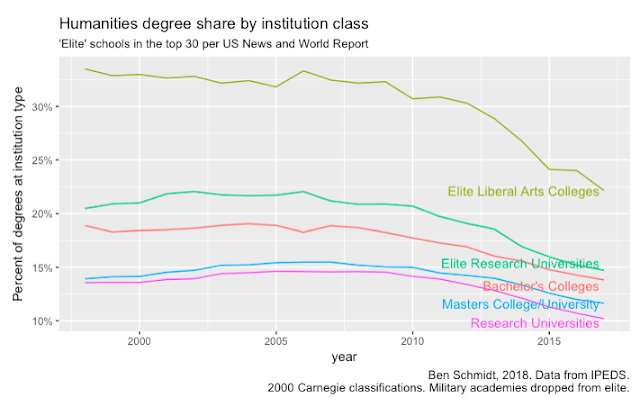

Elite schools matter because they are where almost all humanities PhDs are trained, because they are the only institutions that have historically been especially focused on humanities, and because they tend to unfairly dominate national discussions, and because they present a baseline impervious to the shifting landscape of higher education. Using the top 30 schools in the 2017 US News and World Report rankings as a proxy for quality, here's the breakdown in changes in humanities majors by American Academy classification of humanities and Carnegie classification of schools. (Again, this includes communications and 'liberal studies,' neither of which I personally think are truly humanities fields.)

The elite liberal arts colleges were, until 2011 or so, the only schools where humanities, social sciences, and sciences actually split up the pie evenly: now humanities are down from 35% to 22% of degrees. The drop at elite research universities is similarly steep. (At both, humanities are down to about 70% of their 2008 values.

We can also look at the fall for peak for all the majors that the American Academy tracks at elite universities. Aside from linguistics, communications, and "general studies," all are down by more than 20%. English is down by more than 50% from its 2001 peak at these schools, and history down by almost 50% from its pre-recession peak.

We also know this trend is likely to persist for a few more years, at least. As part of its lawsuit about discrimination against Asian-American applicants, Harvard released information about the intended majors of its applicant pool. The Harvard applicant pool is certainly weird, but is also big (10,000 students) and probably about as good a proxy as we can get for the student body of elite colleges. The class of 2014 (well into the nationwide humanities collapse had about 20% of students intending a humanities major; that share has dropped to about 12%. Only for the class of 2019 do the numbers seem to stabilize.

PhDs are steady, but not coupled to degrees in the long term.

I said up front I don't have a solution. But I should be clear that one thing I would have liked to argue isn't backed up by the data, in the spirit of mea culpas.

I hold the slightly unfashionable opinion among humanities professors that universities should award fewer PhDs in the humanities, and that efforts to "refocus" the PhD into a degree that doesn't only point to academic employment are likely to be much more beneficial to humanities professors than to the students who spend 8 years in them. (For instance; the American Academy recently found, although they didn't frame it in these terms that humanities PhDs in non-academic employment are twice as likely to be dissatisfied with their jobs as those who stay in the academy, while in every other field of education non-academic employment is just as rewarding.)

During the 1970s drop in humanities degrees, humanities PhDs halved in number. I would have liked to exploit this crisis to argue we need to do that again. But in fact, PhDs have leveled out, and the long-term variability of phd numbers mean that the BA to PhD ratio is at an unremarkable level--it's dropped 20% from 2008, but is higher than at any point before 2000.

Am I wrong again?

I was too complacent in 2013: am I being too pessimistic now? Maybe. There are plenty of ways you can squint and think the data is leveling out. I certainly don't think the steep declines of the past decade can continue for another decade.

I may also be over-dismissive of course enrollment numbers, since they're harder to get. AHA surveys show history department enrollments dropping by about 9% since 2014. This is bad, but not as catastrophic as the major numbers. (Although: we don't know what happened from 2008 to 2014, which might matter more.)

But still: I think any empirically-inclined person needs to be more pessimistic than they were five years ago.

But still: I think any empirically-inclined person needs to be more pessimistic than they were five years ago.

Appendix: Supplemental charts

A few supplemental notes that I may expand.

1. There's not a very strong racial component, but there are a couple interesting facts about African Americans. First is that HBCUs have not seen the declines that affect most other institution types (albeit from a low baseline.) Second is that black men show much less change in their humanities inclination than any other demographic group. I do not have any explanation of this.

I have a hard time thinking this is a bad thing. While people should be free to study whatever entertains them, I think most of these majors contribute little to making the world a better place or making us better people.

ReplyDeleteTwo exceptions, in theory, are History and Philosophy, because knowledge in these areas has the potential to improve the quality of thought and discourse. However, the views of most people on these subjects seem to be so guided by partisan identities that it's not clear that mere education can overcome that. People refuse to reason well because they want to fit in with their friends and family.

this is because you dont know much about these majors lmao

DeleteIt sounds like you either haven't studied Humanities or followed a very bad program.

DeleteInteresting that those of you who claim to admire the humanities can't even construct an argument to defend them. Instead, you resort to "ad hominem". Another datum to support my thesis.

DeleteHistory and philosophy are often very much part of the core of study for other humanities disciplines (not that I agree that they are the only justifiable disciplines). I think this is frequently misunderstood. For instance, someone with a Ph.D. in German studies most likely knows about german literature, culture, history, intellectual history, etc. That would be the case for me. Additionally, that person most likely also works in cultural studies and studies, for instance, environmentalism, gender studies, etc. So, as for whether or not the humanities contribute to society, I would argue that the answer is clearly yes because they generate knowledge about the way the world works and how it might be bettered.

DeleteIf we’re asking about who contributes to society more, I think that’s a silly question. People seem to forget that the humanities generate knowledge just like the sciences. It’s the sciences that are more often corrupted by company money. I am actually more concerned about all the scientists and doctors who do research strictly to show questionable results to please big pharmaceutical companies.

My first, mostly uninformed opinion is that, given that it seems perhaps to have been triggered by the Great Recession, it could be a result of the rising tide of student debt. If you think you will have five-figure (or even six-figure in some cases) debt levels when you graduate, and you have an older sibling or friend who got stuck with that after 2008, you might switch to a field that you believe to be more likely to pay off afterwards. Also, parents might be leaning on their kids more in that regard, after 2008 convinced them that a college degree is not guaranteed to pay off if it is in the "wrong" field.

ReplyDeleteThe solution then would be to help Humanities majors get better jobs after they graduate. What is the Humanities style way to do that? I have two engineering degrees, so I couldn't say. But it probably would have to involve at least a little bit of "try harder". Not on the graduate's part, but on the department's part. Many graduates don't really know how to find a job that utilizes their degree. If the departments they got them from don't know how, they should, and could, since they can utilize the information they get from every previous graduate who got one. If declining enrollment provides a sense of urgency, then perhaps the departments in question will get out of their comfort zone a bit more and engage with potential employers more?

A degree/education should not be about money in the first place. What you learn in life is not necessarily marketable nor should it be. If we want a trade school system, we should just convert everything to trade schools and be honest with ourselves as a society in that what we care about is money.

DeleteI agree. As I told my introduction to humanities students last week in today's society one of the biggest transgressions one can make is pursuing education with the intention of educating oneself rather than merely to market oneself.

DeleteIf you are taking out a loan to get the degree, then it becomes about money, whatever your opinion before. The larger the loan, the more urgent the monetary aspect becomes. One more reason why using debt to pay for our post-secondary education system is problematic.

DeleteUnfortunately many students don't have the luxury of ignoring their financial situation. Some friends of mine feel like they were pushed into universities by their high schools or parents and are now stuck with the debt. My second major in undergrad was philosophy so I'm 100% for the humanities, but the current way college is structured simply doesn't work for many people.

DeleteRepeating something I said on Twitter: concerns about the economics of college are certainly a big part of this, but tuition increased linearly even when humanities were stable (1990-2005). I think it's, at least as much, perceived opportunity cost: even if college was free, many kids would feel they had to do STEM.

DeleteHumanities departments are always trying to sell themselves as creating better citizens, rather than preparing for specific jobs. What evidence is there that humanities education makes better citizens? My humanities courses were completely irrelevant to my life experiences and the crises I faced in life. I had nothing to learn from Hamlet or Jane Austin or Descartes. The human condition changed considerably since then, and the they are as irrelevant as hunter gatherers are to New York City residents.

DeleteI completely agree Ross. And I think the idea that paying more attention to practical professional guidance for humanities majors is at odds with appreciation of the intrinsic value of humanistic study does not hold water. People need to appreciate culture on a deeper level AND they need to make a living. We should be selling the intrinsic value first and foremost without neglecting the practical economic considerations while also critically assessing economic assumptions in the spirit of the comment from "unknown" here. I can also understand why many humanities faculty who feel their backs against the wall responding defensively--so now I need to be a career counselor too? Not necessarily. I think much could be gained from working more closely with the career center, the folks whose job it is to guide students through the process of getting a job, but may not have any sense of the practical skills humanities majors possess or where they can be put to good use. Regardless of the strategy, I think we ignore the economics and double down on purely intrinsic arguments (which many find elitist) to our ongoing peril. I think the American Academies recent Humanities Indicator reports that take a hard look at the income and job satisfaction data to demonstrate that it's not as bad as the Starbuck's-barista-with-100k-in-debt-and-a-philosophy-degree trope makes it out to be is helpful in this regard, as is this thorough and insightful analysis Ben. Thanks very much for it!

DeleteOne more supporting point to add: the Humanities Indicator data I referenced shows that some humanities majors do struggle to land their first "real" job, and one can easily imagine how the discouragement and desperation that can bring can lead to a downward spiral. But humanities majors often thrive long term in both the "managerial" and "non-managerial" professions referenced in another post, with many rising to leadership positions. Some of these folks even offer powerful testimony of how their humanities background gave them creative and critical thinking advantages that enabled them to be a "thought leader" in this or that field. I think engaging these kinds of data enable us to have more nuanced conversations with students that actually address their fears--you may have to work a little harder early in your career to find your niche, but if you persevere through that there is reason to believe you may be more fulfilled in what you find and also plenty successful. I think developing these kind of counternarratives more could help us convince more of the students who really want to study the humanities to press on through the naysaying they are certainly exposed to.

DeleteBen, I don't think tuition is the right variable, though. High tuition and high loans become particularly onerous when paired with poor job prospects, especially with the standard jokes about humanities majors being useless.

DeleteI wonder how the trends would map onto (first job salary)/(student loan debt upon graduation)? Rising debt combined with poor job prospects due to the 2008 crisis could be a one-two punch that drives this number down rapidly and drives students to "marketable" majors.

I don't want to be too obtuse here; students with extensive loans probably are more responsive to common knowledge about what majors won't pay. But I think it's less a one-two punch with the recession, and more a like a shove, followed by getting hit by a bus. I think that even if tuition hadn't gone up, students would have left the humanities. I see this at schools like Pomona and Princeton, which give generous financial aid without any loans, but which still saw their humanities share clobbered.

DeleteOr the cost could be reduced. Maybe :cough cough: make university a public good. You know. Like in Europe...

DeleteThanks for this excellent overview. I wish something similar could be done for the European Union, so that we could see how the Bologna Process since 1999 has worked out.

ReplyDeleteThere are OECD statistics on the humanities as a share of tertiary degrees in a large number of countries. https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=EDU_GRAD_FIELD. I've looked into them several times, but have never figured out how to assemble them into a coherent time series. It's certainly possible. Peter Mandler has done some work on Great Britain and *not* found comparable declines there.

DeleteI agree with Wouter Hanegraaff's comment but would extend it further than the EU. I also think this might help to answer ross's opinion that "it could be a result of the rising tide of student debt," particularly if countries are associated with different higher-education costs/debts per student (my children's college education is currently basically free).

ReplyDeleteAn excellent point. Also, do different levels of unemployment in the different countries of the EU (Germany vs. Greece, for example) correspond to different shifts away from the humanities?

DeleteStudents (and their parents) seem to put a lot of stock in internships. Humanities fields do not tend to connect students to those “opportunities.” I’m not arguing that they should, but it is the fashion. I won’t be surprised if a struggling college or two dispenses with most faculty and just becomes an internship coordinator.

ReplyDeleteAnother point: university administrations have been trying to speed up the pace at which students graduate. The advising staff discourages students from taking any “extra” courses in a subject outside of their major—and those “extra” courses turned into second majors or even majors in the humanities. Language requirements have been cut back severely, also to help students graduate faster.

It’s not the quantity, it’s the quality, and Allan Bloom covered that decline fabulously three decades ago.

ReplyDeleteQuantity matters when the drop results in too few bodies to sustain a department or decimates a department.

DeleteI think it might be useful to consider how to place your empirical conclusions here with some kind of theoretical perspective. Why? Why are we witnessing this decline? One can take a neoliberal free market perspective and say this is merely the forces of the market at work; one can psychologize and say it has to do with parental pressures to be "practical." I tend to try to pursue the why question through a hypothesis about class and power: what we are witnessing is a battle between two fractions of the elite: professional-managerial types (corporate, finance, lawyers, tech-oriented elites connected to business elites in the provinces) and professional-non-managerial types (teachers, careworkers, social workers, non-profit types). Of course many individual people are more complicated in their commitments to the humanities, however, at the structural level this might be one way to view the intra-class conflict and struggle going on as it plays out in choices about "majors" in undergraduate education. I emphasize this is just a hypothesis here, testing out a way of interpreting the "why" behind these numbers at a structural level...but I think we need to push toward this kind of theoretical level of interpretation to make the empirical effort worth its salt (but that might be my humanities education talking there!). Michael

ReplyDeleteWell, I think that this kind of theoretical interpretation is already happening already in many different places, but using theories that are not responsive to the actual changes. (See the comment above, which requires a twenty year period of nothing happening after The Closing of the American Mind.)

DeleteAbout the distinction you lay out: it's not clear to me which side you think the humanities are on! I assume the careworkers, because no one would *want* to be on the side of finance. But I think one could make a stronger argument that historically the university humanities have flourished through the forbearance of fields like finance, law, and the national security state; and as each of those has abandoned the disciplines, we're left without patrons in positions of power. After all, nursing majors are doing great, and there's still a shortage of nurses. Why should they help us?

Along these lines, I think that the answer has to include, at least as a proximate, what you call "psychologizing." This is because I believe the financial crisis is proximately to blame. (The only other event of world-historical importance around 2008 is the smartphone; I'd love to read someone blame it on the argument 'why major in history when you have Wikipedia in your pocket?', but I can't do it myself with a straight face). And the generation that grew up in its shadow didn't feel it could afford to take any risks, and makes choices out of anxiety. IOW, "Millennials are killing the humanities."

Why were things ready to collapse in 2008? I don't have a super-interesting contribution to this conversation. Maybe Allan Bloom *was* right, and we only kept the boat afloat for twenty years through grade inflation before the scam was revealed. More likely something about the inability of the university to maintain some of its isolation from the economy in the face of neoliberal pillaging of public goods. If we can't have public education, or subways, or paid maternity leave, why should anyone get to cultivate their ability to read poems?

I agree with what you write here. My thought was that the struggle over public, public goods, role of the state, patronage, obligation, citizenship is a complex struggle going on within different fractions of elites. But this is just a start on trying to explain it. You start to tease out more of the analysis here. Thanks!

DeleteRe: smartphones. Having Wiki in your pocket doesn't make you want to stop writing essays; it helps you with them. Try social media as a substitute for the spirit of inquiry, fellowship and meaning that fuels enthusiasm for humanities (I'm a Ph.D. in Comp Lit). Perhaps social media - exploded after 2010 and the arrival of the iPhone 4 - replaces the sense of belonging and satisfaction with likes and spurts of dopamine. I'm making no normative judgments, here. There's also the matter of (I believe documented) shrinking attention-span as a result of same.

DeleteBut mostly, my money's on money. Cripplingly expensive unless there's a chance of paying down debt - esp in US as undischargeable through bankruptcy.

Just my two cents!

Just pointing you to this piece https://profession.mla.hcommons.org/2018/05/21/the-sky-is-falling/ which makes many of the same arguments you made (and maybe falls into some of the pitfalls you identify).

ReplyDeleteFor what it’s worth, Justin Stover’s intriguing essay related to this topic: https://www.chronicle.com/article/There-Is-No-Case-for-the/242724

ReplyDeleteYeah I really like this essay, though I don't agree with all of it. I re-read it while writing this post.

DeleteThis comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDeleteKids are responding to rising college costs and horror stories of ruined lives from $100k+ student debt loads by shifting toward degrees that will improve their earning power. This seems like a rational and necessary response.

ReplyDeleteOf course employment is always a factor. Also, though, while the true radicals may continue pursuing gender studies, …, the subject matter (radical pomo, critical theory, …) from those departments has without doubt invaded the other arts departments. Try teaching multiple courses over four years in an English major while denying and mocking the ideas of heroes and goodness, replacing them with power and oppression at every turn, and see what the students think. Reap what you sow ...

ReplyDeleteCollege is free in Germany, whould love to see the numbers there

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDeleteAs a Mechanical Engineer and professor, perhaps I can help.

ReplyDeleteThe golden age of the Humanities was in the old, racist past, which ended with the civil rights era. In the old version of history, you promoted 3 ages of European history: the 'golden' Classical Age, the bad Middle Ages (too much Christianity!) and the 'Enlightenment'. You claimed that whites were on top because they were somehow superior.

We can all be thankful that era is in the past. The 'knowledge' was fraudulent, i.e. Humanities were a fraud. Rather than search for the truth and admit your mistakes, you got in touch with your white savior complex. The racism wasn't due to Woodrow Wilson or H. G. Wells. according to you. It was ALL due to some preachers in the wilds of Mississippi with a hundred followers. They were MUCH more influential than Mr. Wilson.

That scam is now uncovered. You would like to neglect money. You forget that no one disproved Alchemy. People just stopped funding it because it gave no return on investment, just like Humanities. The fact that intelligent Humanities students are able to get jobs should not delude you into thinking that you had much to do with their success.

Right now, ABET accreditation standards provide the only life support for the Humanities. My students regard these as junk courses.

Humanities is really a secular religion. It has failed, and everyone can see the failure. Either teach something truly relevant or go out of business. You do not want to learn and teach something new, so going out of business seems to be the preferred option.