It's Monday, so let's run last night's episode of Downton Abbey through the anachronism machine. I looked for Downton Abbey anachronisms for the first time last week: using the Google Ngram dataset, I can check every two-word phrase in an episode to see if it's more common today than then. This 1) lets us find completely anachronistic phrases, which is fun; and 2) lets us see how the language has evolved, and what shows do the best job at it. [Since some people care about this--don't worry, no plot spoilers below].

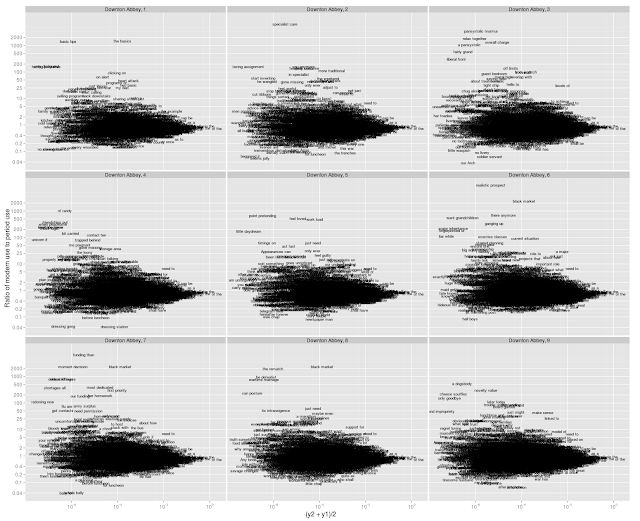

I'll start this with a chart of every two-word phrase that appears in the episode, just like last time. Left-to-right is overall frequency; top to bottom is over-representation. Higher up is representative of 1995 language; lower down, of 1917. Click to enlarge.

So: how does it look?

In short: not too bad. This was one of the best episodes of the season, anachronism-wise. Last week, "black market" was grossly, terribly wrong. This time, there are no unquestionably anachronistic two-word phrases at all. The algorithm's only suggestions, 'dogsbody' and 'cheese souffles,' are both plausible candidates for extremely rare spoken words that just don't make it into the written record out of chance.*

*Though to be completely pedantic: "Dogsbody," generalized from a naval term to mean 'menial worker,' is probably a tiny bit early. It's not attested in the OED until two years later. Though it was probably already present in spoken English somewhere, it seems unlikely that the Daisy, the character who says it, would be on the cutting edge of bringing seafarer's language ashore.

How do I know it's the best episode? Well, I'll quantify that a bit more towards the end of the post, but you can actually see it just in the shape of the cloud. Here are the wordclouds for every episode of Downton so far. (PBS aired 7 episodes, but I have 9 here; that's because episodes 1-2 and 7-8 in the British version were condensed into a single, longer episode for American audiences, I believe). You can click to enlarge and find some of the modern language (towards the top) and most period-characteristic (towards the bottom) in every episode, but even in thumbnail form, you can see that there aren't that many words up high in last night's episode (lower right) compared to, say, episode 6 (middle right).

Nonetheless, there's quite a bit that happens that's off. Even when writers do their best, the English language has drifted on in all sorts of directions.

The single biggest anachronism this week is probably the phrase "novelty value," which one character talks about regaining by skipping lunch. "Novelty value" is doesn't enter British English until the 1930s. There are very a few uses before 1920, but most are part of the phrase 'novelty, value, and usefulness' in American legal language. (Which may the origin of the phrase, but that's neither here nor there.) The very few uses of novelty value I can find before 1922 don't use it with weary cynicism, but with enthusiasm. The bloom isn't yet off the rose.

Premature cynicism is an interesting feature of Downton Abbey, actually. One of the outliers I noticed in the season premier was the Earl of Grantham speaking warily about the "brave new world" coming after the war. The algorithm senses a problem: Huxley's novel wasn't until 1931, making the phrase far more popular. OK, you and I both say: but "brave new world, that has such people in it" is from The Tempest, and surely the Earl knew his Shakespeare. But there's the problem: Huxley cut Shakespeare's line in half: until 1931 "has such people" is as common as "brave new world", but afterwards the latter trigram takes off. Accordingly, most pre-1931 uses are about new people, and most post-1931 ones are about new social arrangements. The Earl's usage is ironic, and about social arrangements: therefore I'd say the numbers are right that it's an anachronism. But what's really interesting is that a lot of the time, ironic remarks may be the places where writers are most forced to take in modern sensibilities, because irony just won't translate.

Other than novelty value, though, there aren't many howling anachronisms this week. "Board games" is not strictly anachronistic--it shows up in an American magazine ad during the war, and the novelty of the Ouija board is a big aspect of the episode, so using a rare new word might be OK. On the other hand, it takes a pretty capacious definition of 'game' to easily classify Ouija as a 'board game' (there even appear to be court cases about just that), and I sort of doubt that the phrase would have immediately jumped to mind. And the 3-word phrase "play board games" doesn't occur until 1960, so I guess I'll issue a warning. "Trouble understanding" is another problematic but acceptable phrase: it's almost 100x as common today as in 1920, but it did exist.

But what's really interesting for me are the more common words that get suggested as anachronistic. The big example this week is the phrase "make sense." Google books suggests, and Bookworm confirms, that "make sense" is most common in psychology in the pre-Downton period; it doesn't really take off until after 1925 or 1930. A more appropriate choice than 'doesn't make sense' might be 'isn't clear' or 'is nonsense' (the latter is less common than 'make sense' today, but 100x more common in 1922.)

But for me, the big prize on this chart "just might." I've spent the weekend asking everyone I know if there's an important semantic difference between "might just" and "just might"; I've heard a few good answers, but it seems like most our ears can't distinguish between the two. Today, "just might" is about half as frequent as "might just"; but it was only about 1.1% as frequent in 1920. (Non-words like 'just just' and 'might might' are equally common in the Bookworm corpus). I can't for the life of me distinguish between those two; I'm not sure one even sounds more modern than the other. But the numbers are pretty clear here: it should definitely be 'might just' in 1920. No question about it.

This, to be honest, is the sort of thing that I'm most interested in finding. I'm fascinated to see how the language changes in directions that we don't notice. Historical accuracy is, of course, not the primary virtue of television, but it is one virtue: and every little distinction like this makes the past seem more alien, everything that changes with the passage of time more strange. We can watch TV shows to people behaving just like they do today: but why not see just how different things were?

Toward that end, I grabbed a bunch of other scripts from online of English period dramas set in the reign of George V. (In most cases, these are extracted subtitles). For each one, I extracted two different statistics: the percentage of extremely anachronistic language (fairly common today, and more than 64 times as common today as when the show/movie is set); and something else approximating the share of somewhat modern language, roughly words 10x as common when the script was written as when it was set). I tossed out the most common spelling changes ("any one" to "anyone", for example), curses, and dialect like "gonna."

To this set I added one actual Georgian drawing room drama: George Bernard Shaw's Heartbreak House (1919). Several people said in response to my last post that language enters the spoken language before it enters the written one. True, to a point. But plausibility and accuracy are two different things. Maybe words enter the language through speech first. (Although in of Downton's mistakes--"pansystolic murmur," for example--the print form probably came first). Certainly the mistakes may not require one to suspend disbelief too much. But if we want to know what the past sounded like, I can see no reason to believe Julian Fellowes has a better grasp of spoken language from 1919 than did George Bernard Shaw.

Anyway, here's the result:

What do we learn? Heartbreak House is indeed the best on the two metrics combined (that is, closest to the lower left); but even it has a few words that are pretty extreme outliers. The Remains of the Day actually has fewer extreme outliers than Shaw. Checking for moderate outliers as well makes Heartbreak House clock back in where it should.

As for Downton Abbey: you can see that episode 9 is the closest to Heartbreak House, which is why I say it's one of the best. Also, it's nice to see that the individual chunks of Downton and of Heartbreak House are relatively coherent; that means the gaps between the shows are not just statistical noise).

How does Downton Abbey compare to other scripts? Well, Remains of the Day beats Downton on both scores; Howard's End has fewer extreme outliers, but a few more moderate ones. This may partly be because it's set a decade earlier, which I'm not completely controlling for--but I'd wager that also reflects the difference between the two. (More howling anachronisms in Downton, more overall modern language in Howard's End).

But most interestingly, exactly overlapping with Downton Abbey is "Gosford Park." That movie, you may know, was directed by Robert Altman, but written by the man who went on to create and write Downton Abbey: Julian Fellowes. Ten years later, the strengths and weaknesses are just the same. Even some of the mistakes are the same; just as 'trouble understanding' was one of the worst phrases in Downton Abbey this week, 'trouble sleeping' is one of the worst in Gosford Park.

That's what I find fascinating about the whole thing. All of these writers are trying to speak the language of the past, but it's a foreign one; and they each have their own characteristic slip-ups. No one is truly a native speaker of the old tongue. (Even when, like Edith Wharton, they lived through the age themselves).

Someday maybe I'll post a few more of these. The Deadwood word cloud, in its anachronistic, R-rated glory, is something to behold; for me proof positive that great TV doesn't have to be accurate. But that's enough for now. See you when Mad Men starts up again?

Really enjoyed these two posts. I'd love to see some upstairs vs downstairs comparison - a little class-analysis seems called for in a production that pretends to dramatize a simmering class antagonism and a changing social order at so many levels.

ReplyDeleteThe dowager countess had me for a fan in season one when she leaned her head back and mumbled "what on earth is a 'weekend'?" :-) I looked up "weekend" in Google n-grams and it indeed was relatively rare before the war. But whose language does the n-gram database capture anyway?

Ben, I don't suppose you'd be willing to share the scripts you're using for this? As a writer, I would adore having something like this as a tool to catch my own unconscious anachronisms!

ReplyDeleteI second the request for code examples. Excellent post

Delete@Anupam: Upstairs Downstairs is on the list, now that I'm convinced I can do this without reading the scripts enough to get spoilers...

Delete@Naomi & Shawn; Yeah, I have a medium-term goal to start actually sharing code more, but it will require some cleaning (both for readability and for passwords). The problem in this particular case is that you need to have the whole ngrams dataset loaded into a local database (I already did for other reasons) for this to work; maybe I'll put up a blog post about the whole chain at some point, with the code that makes sense. If there were an API call to Ngrams, this could be run without local storage.

For the visualization aspects, I will put up one bit: the latest version of the code to make the graph. (It looks a tiny bit different than above on the axes). This is all done using R and ggplot2 (and generally trying to follow Hadley Wickham's split/apply/combine strategy); so here I create a data.frame with 3 columns: y1 (% in 1917), y2 (% in 1995, the last reliable year in the Ngrams database), and word1 (the two word phrase). The great thing is that once you have a graph like this in R, you can just add elements depending on the other data present, such as faceting by episode as in the 9-way grid above, by just adding a line like "+facet(~show)."

textcloud = function(plottable) {

#Just a quick thing to convert ratios to numbers, so that ggplot shows pretty ratios rather than logarithmic numbers

labelz = c("300:1","100:1","30:1","10:1","3:1","1:1","1:3","1:10","1:30")

numberplot = function(string) {rel=as.numeric(strsplit(string,":")[[1]]);rel[1]/rel[2]}

#Here begins the graph.

ggplot() +

scale_y_continuous(

"Ratio of modern use to period use",

labels=labelz,

breaks = sapply(labelz,numberplot),

trans='log10') +

scale_x_continuous("Overall Frequency",labels = c("One per ten million","One per thousand"),

breaks = c(1/100000,1/10),

trans='log10')+

#The first text layer is for words that appear finite times in year 1. (here, 1917 or so depending on the show).

geom_text(data=subset(plottable[plottable$y1!=0,]),

size=2.5,aes(x=(y2+y1)/2,y=y2/y1,label=word1)) +

#The second text object is for words that don't appear at all in year 1.

geom_text(data=subset(plottable[plottable$y1==0,]),

size=2.5,color='red',aes(x=(y2+y1)/2,y=400,label=word1,position='jitter')) +

geom_hline(yint=1,color='black',alpha=.7,lwd=3,lty=2)

}

Ben, this is great! Any thoughts on how Mad Men would compare?

ReplyDelete"(I) Might just" would always be followed with what one might just do. Whereas "(I)Just Might" is stand alone, particularly in Lancashire, where I come from.

ReplyDeleteOtherwise love this thing.

I don't think Anupam meant including the 'Upstairs Downstairs' property; I think what was meant was analyzing the dialog of Downton's gentry separately from that of its service staff.

ReplyDeleteOops, you're right. Sorry, Anupam!

DeleteThat would be really interesting, you're right.

It's unfortunately much harder than running a different show; I use subtitles that don't identify the speaker for the text, so someone would have to go through and tag the speakers line by line. (There are a few scripts out there that would make it easier--just tag the speaker names by class--that might be worth doing.)

Ben, I'm guessing you're American? To my (British) ear 'might just' and 'just might' are definitely not the same. The latter means something is quite unlikely; the former could have that sense (and even that might be an imported Americanism?) but it could also mean the same as 'might', with 'just' modifying the following verb to suggest a swift or decisive action. "I might just tell him." "I might just give up."

ReplyDeleteCorrect me if I'm wrong, but I have a feeling that Americans tend to transpose that sort of 'just' to BEFORE an auxiliary verb. You hear people say things like, "Just don't stand there" , which to me sounds quite odd.

@Richard and Liz

DeleteVery interesting--apparently Briitish people hear the difference between 'just might' and 'might just' more clearly than Americans like me. Ngrams confirms that "just might be" (the phrase in the show) is roughly the same frequency as "might just be" in American English, but significantly rarer in British English. Of course, that only makes the American version coming from Isobel, an older British lady with no known connections to America, even worse.

Hi Ben

ReplyDeleteBrilliant work. Of course, there are historical inaccuracies in Downton such as the 'Turkish Ambassador'(rather than the 'Ottoman Ambassador' since the Republic of Turkey was proclaimed in 1923) which Ngrams can not pick up. Or visual ones such as the presence of trees around the World War I trenches.

It always amazes me why such multi-million pound/dollar productions don't employ a lowly researcher to check on such basic facts. Hopefully writers of future costume dramas can employ your algorithm to stop major howlers from reaching our ears.

The tree one is a good catch.

DeleteAs for Turkish ambassador, Ngrams could pick this up: that it doesn't should actually reassure us that this is _OK_ to use (I've heard this put out as problematic before.) Actually, people said "Turkish ambassador" all the time before 1923; here's an example. I think it's even more common than saying "Russian ambassador" during the Soviet Union, which we all know happens.

(I should note that I wouldn't have found it, though, because I didn't include capitalized words in this run because names and places tend to be fictional, and so tend to mess up the data.).

I'd love to see an analysis of patrick O'Brien, i'd wager he'd be comfortably bottom left :)

ReplyDeleteThis is terrific stuff, thank you so much for sharing. As a half Britisher, I agree with Richard and Liz about might just/just might. And as a person often involved in translating from French into English and vice versa, I can't help but think that this tool might be really useful for me. I often enter word combinations I'm thinking of using in translations in Google, to check their frequency, and I'm getting quite skilled at finetuning this, by eliminating websites that are clearly (usually poor) translations and Canadian sites, that have a definition of bilingual, which is in fact an entirely weird separate language! But it seems to me that Ngrams would give me far more sophisticated information. (And yes, I do also use Google Translate as a starting point, sometimes)

ReplyDeleteI am interested in the term used "have done" - is it a Yorkshire term, or rather an overall British term, it sounds redundant to my Midwestern native ears. I am curious as to how the phrasing /idioms compare with those in Lark Rise.

ReplyDeleteThe analysis is fascinating, but the worst anachronisms are those like "learning curve"--used AGAIN in the finale--that today's middle-aged viewers can remember as neologisms.

ReplyDeleteOr "parenting."

DeleteI think that's right, although there a few exceptions. This is last year's post, though! I talk about parenting and 'learning curve' in the season 3 finale wrap-up

DeleteVery efficiently written information. It will be priceless to anybody who uses it, together with myself. Sustain the good work for positive. I will try extra posts. Sydney

ReplyDeleteDownton Abbey Series 1-4 DVD box set is a series about the sorrows and joys of partings and meetings of a big family.The action of the show taking place in the early 20th century.In the large family of Lord for each member of the family and servants of their own role and their own place. In spite of the democratic and peace-loving nature of Lord, no one do not dare to question it. As it should be the will of the tradition after his death, the estate must go away to male heirs, but as the only candidate on the Titanic dies, the family raises the question: what do you do?

ReplyDeleteWill Downton Abbey season 4 dvd box set soon close its doors? Will Mary’s broken heart mend? And will Edith finally find love?

ReplyDeleteThe cast and executive producers of the hit PBS drama gathered at the Television Critics Assoc. press tour in Beverly Hills on Tuesday night to unveil the first footage from Downton Abbey season 4 dvd, debuting Jan. 5. They also offered up some juicy teasers about what’s in store for Lady Mary, Edith, Daisy and the rest of the residents of the famous estate.

Downton Abbey series 4 dvd box set

i love article, greatings Obat Bius

ReplyDeleteI've seen many news articles on the historical inaccuracies of Downton Abbey. I would like to add that in England at the Criterion, they were supposed to have barmaids not bar men. Bar men were only in America. This can be easily seen from 3 stories by P.G. Wodehouse. I think less mistakes would be made by the writers reading the works of Wodehouse.

ReplyDelete